Just last spring, a chorus of pundits loudly proclaimed a sweeping urban exodus and the impending death of cities. Now, just slightly more than a year later, our cities are springing back to life. Sidewalks are starting to bustle; restaurants, which have spilled onto the streets, are teeming with patrons; museums and galleries are reopening; and fans are heading back to baseball parks, basketball arenas and even outdoor concert venues.

But one area of urban life where the pandemic is poised to leave a far bigger mark is on the places where we do business. The ongoing shift to remote work challenges the historic role of the Central Business Districts — neighborhoods like New York’s Midtown and Wall Street, Chicago’s Loop, or San Francisco’s Financial District — as the dominant centers for urban work.

These signature skyscraper and corporate tower districts that define the skylines of great cities, and are often synonymous with downtowns, will have to adapt. But far from killing them off, the shift to remote work will ultimately change their form and function in more subtle ways. Given their strategic locations at the very center of major metro areas, Central Business Districts are perfectly positioned to be remade as more vibrant neighborhoods where people can live and play as well as work — a leading-edge example of what many urbanists are now calling

15-minute neighborhoods. And with conscious and intentional action on the part of urban leaders and assistance from the federal government, these CBDs can be rebuilt in ways that are more inclusive and affordable.

The biggest and most enduring change in our economic geography ushered in by the pandemic turns out to be far less in where and how we live, and much more about how and where we work.

The pandemic effect on work

As 2020 began, the 21 most important urban business districts in the world housed 4.5 million workers in 100 million square meters of office space. About 20% of Fortune Global 500 corporations had their headquarters in these districts, according to a 2020 report by EY. A few months later, the lion’s share of knowledge and professional work was being done from home. In the proverbial blink of an eye, the Central Business Districts of leading cities around the world went silent — emptied of workers and the buzz of human productive activity.

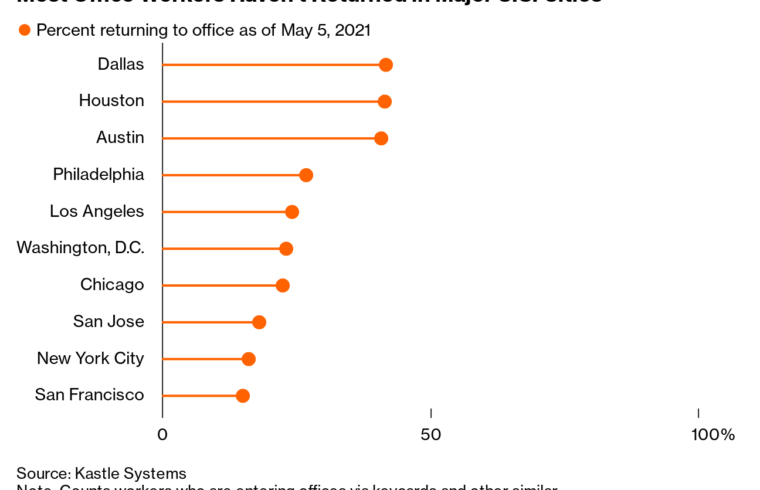

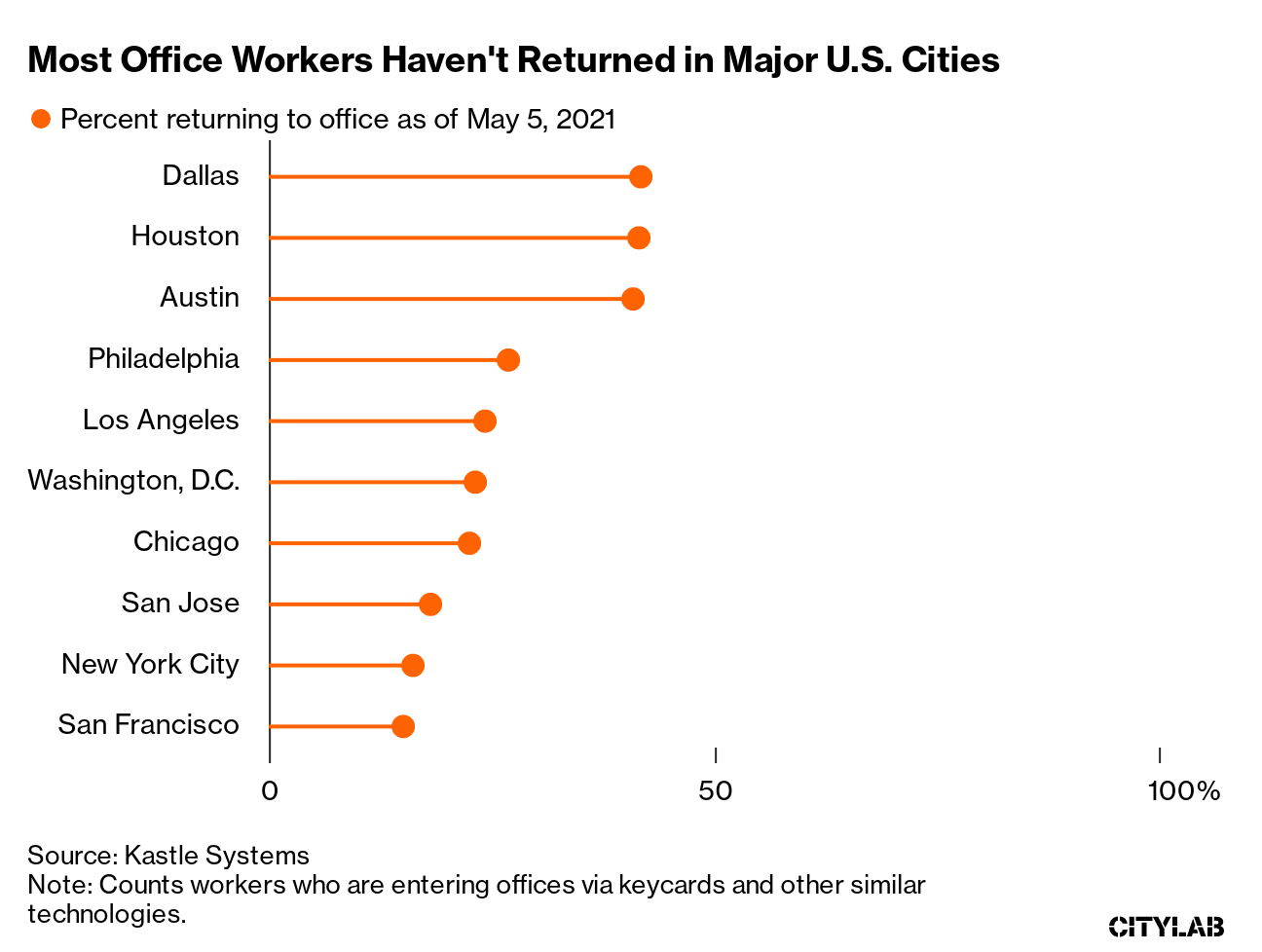

Even as vaccinations have accelerated and America has sprung back to life, these business districts in major cities have been slow to rebound. Across 10 of America’s largest urban CBDs, employee visits to the office stood at roughly a quarter (27%) of pre-pandemic levels according to recent data from Kastle Systems, which tracks these visits through keycards and similar technologies.

Most Office Workers Haven’t Returned in Major U.S. Cities

Source: Kastle Systems

Even in Australia’s cities, which are now near-completely reopened, occupancy rates in the Central Business Districts of its two largest cities remain far off their pre-pandemic levels — hitting 59% in Sydney and 41% in Melbourne as of April.

It’s likely not just the fear of offices per se, but the fear of getting to and from them that remains a fundamental challenge. Though New York City subway ridership has ticked up this spring, it remains at just 40% of pre-pandemic levels. More than a third of Americans remain wary of riding the subway or a crowded elevator, according to a recent study. Even as suburban office parks where people can drive to work begin to fill up, CBD office districts remain far emptier.

Of course, more workers will return to the office in the coming months, as vaccinations progress and the threat of Covid recedes. Ultimately, remote work done from home will likely account for roughly a fifth (21.3%) of all work-days, compared with just 5% pre-pandemic, according to surveys by economist Nick Bloom and his colleagues. This will not just reduce demand for office space — some of which will be made up for by the need for more private offices and large spacing for social distancing; it will hit hard at the broader downtown ecosystem of restaurants, cafes, bars and retail shops that make up the economy of business districts. Bloom and his colleagues estimate that this shift will reduce consumer spending in the CBDs of major cities by roughly 5% to 10% relative to their pre-pandemic baseline, with Manhattan taking the biggest hit — a 13% reduction from pre-pandemic levels.

As with so many other effects of the Covid-19 pandemic, the burden of the transformation and decline of Central Business Districts will fall heaviest on low-wage service workers. Downtown expert Paul Levy estimates that every 500,000 square feet of occupied office space in the CBD creates jobs for 18 cleaning personnel, 12 security staff and 5 building engineers. As the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis has documented, these low-wage, largely minority, largely immigrant service workers have borne the brunt of the economic impact on the CBD, while professionals and knowledge workers have been able to simply shift to remote work.

What’s next for work-centric neighborhoods

The decline of the old-style CBD does not mean the death of the neighborhoods that house them. Their locations are just too good — too central, too dense, and with too much infrastructure and architecture — to remain vacuums for long. And their transformation — like nearly every other aspect of the Covid-19 pandemic — will be less a fundamental disruption and more an acceleration of trends already underway.

Even as our cities have evolved and changed markedly over the past several decades, the CBDs of many major cities retain some of the one-dimensional, work-only 9-to-5 attributes that urbanists like Jane Jacobs and William “Holly” Whyte decried half a century and more ago. We’ve now been through a century-long experiment in building downtowns for worker bees. The reality, as Jacobs said long ago, is that we need to be building downtowns for people. Indeed, urban neighborhoods are the most adaptive and resilient of organisms: Out of urban decay sprout the seeds of new life.

Perhaps the best historical analogue to what the CBD is going through today is deindustrialization. Few, back in the dark days of the 1970s or ‘80s, would have predicted that the old manufacturing areas of the city would ultimately be repurposed and reused not just as arts and creative districts but as tech and knowledge hubs — or that they would become the epicenters of the gentrification that has become a defining feature of superstar cities today. Central Business Districts have attributes — their location, density, transit connectivity and more — that enable them to adapt to this new reality. The bigger challenge is to ensure that as they come back, they become more equitable and inclusive communities.

In the not-too-distant future, more people will start returning to their offices. While many companies have shown a newfound acceptance for remote work, others likeAmazon.com Inc., Blackstone Group Inc. and JPMorgan Chase & Co. have said that they expect a significant percentage of their workforce to return to the office. Big tech companies likeFacebook Inc. and Alphabet Inc.’s Google have doubled down on office space in Manhattan during the pandemic. Even companies that are shifting toward remote work will continue to need physical space for some portion of their workers, particularly to onboard new recruits and acculturate them into their ways of doing business. In fact, many companies have put off hiring during the pandemic until they can get workers back in the office.

Even those who work remotely are not simply holed up in their houses and apartments. According to a recent survey, 22% of people who plan to telework say they’ll do so outside the home, and most of those people plan to spend time at co-working spaces, cafes, restaurants or outdoor public spaces, all of which are readily available in Central Business Districts.

These office districts will have to evolve and change in ways that reflect the changing needs of workers and the changing patterns of knowledge work. Indeed, the office of the future will likely be less a single building in a single location, and more an outgrowth of the urban fabric. It is evolving into a “network of spaces and services tied together with technology,” as future of work expert Dror Poleg wrote in his book

Rethinking Real Estate. An interconnected ecosystem could span not just a central office location but also the home offices, co-working spaces, coffee shops and other third spaces that support remote work in the suburbs or outlying areas.

“People no longer have to be there, which doesn’t mean they’ll all leave,” wrote Poleg. “But it does mean that cities/buildings will have to compete more fiercely and along new dimensions.”

The office as we know it was already in the throes of change and transformation. Some twenty years ago, when I was researching Rise of the Creative Class, I asked young creatives in fields from tech to the arts what they wanted in a workplace. They told me it was the ability to work on great projects, with great people, in great spaces, in a great neighborhood. All of that is even more the case today. The office of the future will be less a cubicle-farm where workers park behind their laptops and more an arena for social interaction. Offices will have to be healthier, more spread out, with more common areas and meeting spaces, and more outdoor work space. Employers will need to ply their remote workers with amenities like exercise rooms and in-house restaurants to coax them away from their home offices, especially on Mondays and Fridays. They will need to offer special programming: not just wine and cheese plates, but onsite training and education, access to graduate coursework, and group fitness and wellness offerings. In headquarters cities, offices will also need to function as branding statements. Companies will do these things for a simple reason — to attract and retain talent.

Amazon’s ‘Helix’ design for its new HQ2 in Northern Virginia will feature indoor and outdoor green spaces. The corporate campus will also include 2.5 acres of public green space, a dog run and a 250-seat amphitheater.

Source: Amazon

This culture will extend far beyond the four walls of office towers. The CBD can no longer function as a collection of low-end grab-and-go cafeterias, chain coffee shops, restaurants and salad bars. To evolve and survive, its offerings will have to become more local, authentic and actively curated. A day at the office will be spent less in a single building and become more like a localized business trip, with maybe an onsite meeting, checking some emails at an outdoor workspace, doing a group fitness session with colleagues, and taking some offsite meetings over lunch or coffee. The downtown expert David Milder dubs this as a shift from the old Central Business District to what he terms the Central Social District, in which workers and people meet, collaborate and socialize together. As I see it, the Central Business District will evolve into a hub in a system of more decentralized Neighborhood Business Districts that span from the city center out to the suburbs and rural areas. Far from being dead, the CBD is perhaps the single best place to be transformed in this way.

Central Business Districts are the most centrally located and densest of all urban neighborhoods, and those in the biggest metro areas are well situated to take advantage of the tight clustering of talent and economic activity that economists call agglomeration. The tendency of people and ideas to concentrate in certain urban areas and neighborhoods is so powerful that the Nobel Prize-winning economist Robert Lucas identified it as the most fundamental force behind innovation and economic growth. While remote work may weaken the pull of geographic clustering that has defined the knowledge economy, it will not kill it off. As the leading urban economist Enrico Moretti recently put it, “everything we know from economic geography before Covid tells us that these forces of agglomeration are quite powerful. And there’s no reason to think the same tendency to cluster will be all that different in a post-Covid world.”

Yet, real innovation of this sort also tends not to take place in skyscraper canyons. In the past, the CBD was more of a place to pack and stack corporate professional workers in management, law and banking than a center for innovation and creativity. It was an outgrowth of the extreme separation of work from life that characterized the industrial age, the workplace analogue of what similarly specialized dormitory suburbs were for living. And therein lie the seeds of new life — in overcoming that separation and remaking CBDs into more vibrant places.

A woman works on her laptop at an outdoor table in Flatiron with a view of the Empire State Building in the background. As demand for office space drops, urban business districts will have to rethink old ideas about where work gets done.

Photographer: Alexi Rosenfeld/Getty Images

When my research team and I looked at the leading startup neighborhoods in the U.S. in 2016, not one was a CBD as traditionally defined. Many were urban mixed-use neighborhoods like San Francisco’s SOMA and the Mission District, and New York’s SoHo and Chelsea — higher-amenity neighborhoods that were key to

attracting new residents to live in central cities. Some of these neighborhoods, like those south and east of Midtown Manhattan, sit just on the border of what we think of as the traditional business districts. But instead of being office-centric, they’re defined by a mix of live, work and play in a walkable setting. That’s because what drives innovation and startup entrepreneurship is not the density of jobs or offices but the density of talent — talent that can mix and mingle, and combine and recombine amid the clash, clamor and collisions of street-level density.

The CBD can be remade along these lines. In fact, many were evolving in just this direction before the pandemic, adding more cafes, restaurants, arts and culture, boutique hotels and other third places — not to mention lots more co-working spaces. A 2013 study documented shifts to more mixed-use, vibrant, live-work downtowns in cities of all shapes and sizes that were happening a decade ago. Take the case of New York’s Financial District around Wall Street, as it was rebuilt in the wake of the tragic devastation of 9/11. In 2000, 24,000 people lived south of Chambers Street; more than 60,000 do today. In Philadelphia, nearly 200 vacant office and industrial buildings in the downtown core have been converted to housing or hotels.

A man cycles past the Oculus transit hub in downtown Manhattan.

Photographer: Angela Weiss/AFP/Getty Images

Going forward, cities need to be intentional about how these business districts evolve: Left to their own devices, they will be remade in a way that benefits the already advantaged and deepens existing economic, social and racial divides. Instead of only providing incentives to landlords to convert fallow office towers into high-end residences, urban policymakers must ensure they’re also converted into much-needed affordable housing. They must provide more opportunity for minority-owned businesses, and ensure that displaced and/or low-wage service workers have access to higher-paying family-supporting jobs in the CBD and elsewhere throughout the city. The federal government with its stimulus and related spending can and must be a partner in this effort. One model to look at is the partnership the city of San Jose, California, worked to forge with community activists, neighborhood groups and Google to rebuild its downtown as a more inclusive neighborhood with offices, restaurants, cultural venues and 1,000 units of affordable housing, with a contribution from Google of $200 million.

We have a once-in-a-century opportunity to turn our business districts and our cities into something better, less divided, and more inclusive. Shame on us if we fail to grasp it.