Key takeaways:

- As the Delta variant of COVID-19 spreads throughout the United States, Arkansas and Missouri are facing an even more dramatic spike in COVID-19 cases, in part due to lower vaccination rates. This puts many at risk and may contribute to long-term economic problems in the region.

- To mitigate these effects, Missouri and Arkansas policymakers must take immediate action to strengthen public health and the economy, including:

- Expanding Medicaid and eliminating barriers to benefits.

- Recommitting to the federal expansion of unemployment benefits to cushion the economic harm as business disruptions grow.

- Enacting paid sick leave and paid family and medical leave.

As COVID-19 cases and hospitalizations begin to rise again across the country, some states are more vulnerable than others. Neighboring states Missouri and Arkansas are in the middle of a serious COVID-19 spike along with Louisiana, Florida, and Mississippi. The number of cases per capita in the two states—about 52 new cases daily per 100,000 residents in Arkansas and 40 per 100,000 residents in Missouri—is more than twice the national average of 19. The seven-day rolling average of deaths in the two states is rising rapidly and is three times the national average. Mercy Hospital in Springfield, Missouri ran out of ventilators over the Fourth of July weekend. Hospitals across the state of Arkansas are already reaching maximum capacity—even as a record number of COVID-19 hospitalizations are anticipated in the coming weeks.

The new Delta variant of COVID-19, which has caused new lockdowns in Australia and Malaysia and caused some nations to restrict incoming flights from Britain, has spread throughout these two states and is now the most dominant strain of the virus throughout the United States.

Both Missouri and Arkansas are lagging behind the country in COVID-19 vaccinations, the primary factor in lowering the risk of hospitalization. Across the United States, 55% of the population has at least one shot, but in Missouri that rate is 47% and in Arkansas 45%. But even those numbers belie the situation in Arkansas’s northern and Missouri’s southern counties—most are below 30% fully vaccinated, and just 17% of Reynolds County, Missouri is fully vaccinated, including just one in three people over 65.

The policies in these states today also undermine efforts to take the pandemic seriously and reduce the spread of COVID-19. Both states have eliminated mask mandates. Arkansas Governor Asa Hutchinson lifted the state’s mask-wearing mandate on March 31, 2021, and a law going into effect later this month will prohibit the governor and the public health department from using its authority to reinstate a mask-wearing mandate and declare a public health emergency. The policy also prohibits local governments from enforcing mask mandates, though private businesses are permitted to require masks if they choose.

Recognizing the risks of the highly transmissible Delta variant and low rates of vaccination, these two states must act quickly. While the risks are lower for people who are vaccinated, there are still segments of the population not yet eligible for vaccines, and vaccinated people—especially those with underlying health conditions—remain at risk. People of color in Arkansas and Missouri are more likely to have underlying health conditions and work in front-line occupations and industries in health care, child care and social services, and grocery and food production due to occupational segregation. Because of ongoing systemic racism, Black, Indigenous, Pacific Islander, and Latinx people have experienced the highest death rates from COVID-19. This spike is happening in rural parts of both states that still had not fully recovered from the Great Recession of 2007–2009 when COVID first struck, and this resurgence in cases may contribute to more long-term economic problems across the region without prompt action.

In addition to public health measures recommended by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and other medical experts, Arkansas and Missouri policymakers should take a number of actions described below to deal with the uptick in economic disruption and dislocation this summer wave will cause.

Expand Medicaid and eliminate barriers to benefits

Missouri’s legislature should begin by approving funding for the Medicaid expansion approved by Missouri voters in 2020. So far, in a transparent attempt to undermine the will of the electorate, the legislature has refused to appropriate the money needed to expanded Medicaid, a decision currently under litigation. Medicaid expansion has only been more critical during the public health and economic crisis, providing insurance coverage for people who lost their jobs along with their employer-provided health insurance.

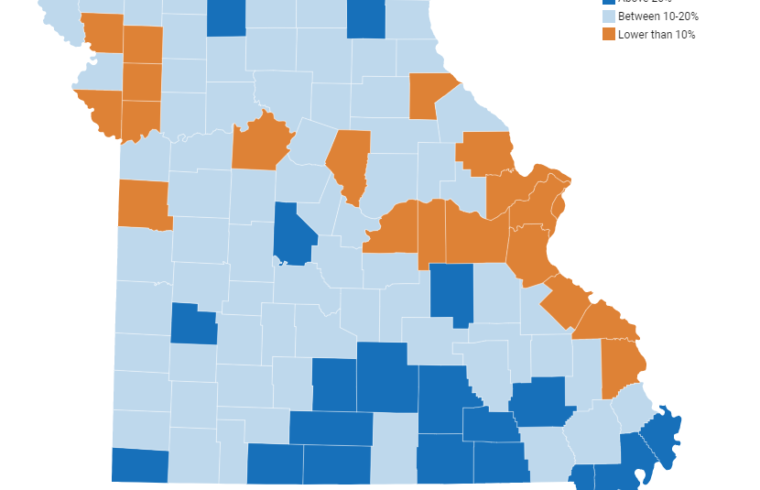

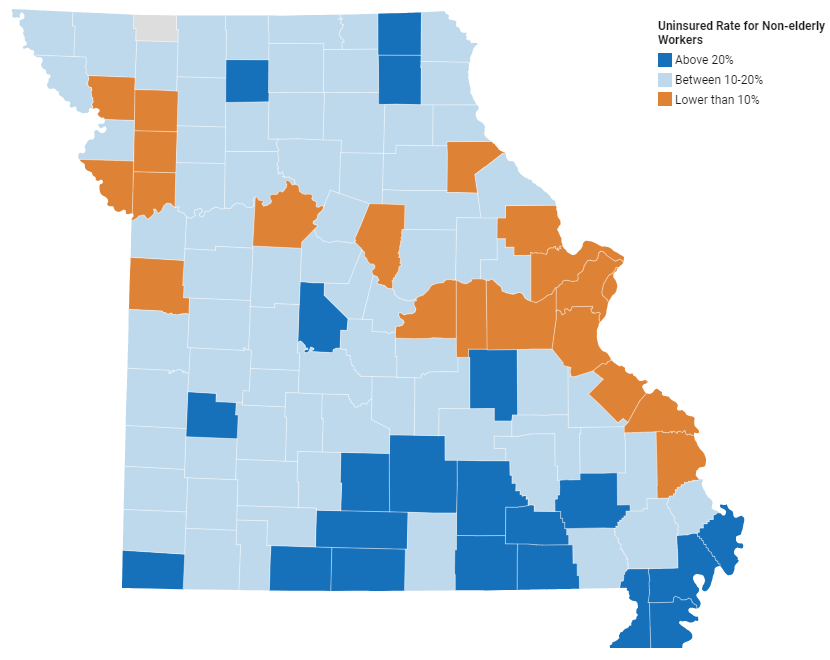

As the Missouri Budget Project has shown, the uninsured rate for non-elderly workers in Missouri is highest in those same southern counties now impacted by the new wave of COVID-19. During the first six months of the pandemic, according to Families USA, a 10% increase in a county’s uninsured rate was correlated with a 70% increase in COVID-19 cases and a 48% increase in deaths from COVID-19. People without health insurance are more likely to delay seeking care, and with COVID-19, every day increases the risk of further disease spread. Adding 275,000 new Missourians to Medicaid would have an appreciable impact on both the spread and treatment of COVID-19.

Credit: Missouri Budget Project

Credit: Missouri Budget Project

Beyond Missouri’s southern border, the Arkansas General Assembly renewed its Medicaid Expansion program thanks to advocacy and community-based organizations that supported the program throughout different legal challenges and also demonstrated the impact of harmful work reporting requirements. A 2020 report by Arkansas highlights how the passage of the Affordable Care Act and Medicaid expansion led to the third highest drop in the rate of uninsured people in the country. However, during the past legislative session, Arkansas—the first state in the South to expand Medicaid—also became the first state in the country to pass harmful measures that would make it easier to discriminate and deny health care services to LGBTQ+ communities. These measures should be reversed.

Restore federal pandemic unemployment insurance benefits

The economic situation in Missouri is likely to get worse before it gets better. Even if the state does not mandate lockdowns or similar measures, a resurgence of COVID-19 cases will slow economic activity in many ways. This means, among other things, making sure that unemployment insurance is available for all who need it.

Unfortunately, the Missouri state government seems more interested in stigmatizing unemployment benefits than helping workers in need. Some 46,000 Missourians accidentally received overpayments of unemployment insurance. The U.S. Department of Labor has told the state it is not necessary to seek repayment of erroneously paid funds, and the Missouri Department of Labor has announced a waiver process for the federal dollars, but the situation is far less clear for overpayments of state funds. The Missouri House passed a bill to forgive the debts by a resounding 157-3 vote, but the Missouri Senate adjourned without taking a vote on it, leaving thousands in the lurch. The state budget did allocate $40 million for those repayments, but a waiver process has yet to be announced and it is not certain there will be one.

While the legislature was failing to act, Missouri Governor Mike Parson ended the state’s participation in federal pandemic unemployment benefits, including the $300 weekly boost to benefits, in June. Arkansas ended its participation shortly thereafter. As EPI has already noted, such a decision is “dangerously shortsighted.” Roughly 120,000 fewer people are employed in Missouri than before the pandemic. In Arkansas, nearly 50,000 fewer people are employed. Workers who are unable to rely upon unemployment benefits will be more reluctant to stay home from work to prevent the spread of the disease. Missouri and Arkansas should recommit to the federal expansion of unemployment benefits to cushion the economic harm as business disruptions grow.

Implement paid sick leave and paid family and medical leave

A final step Arkansas and Missouri policymakers should take is enacting paid sick leave. Workers exposed to COVID should not have to choose between working while sick or being unable to pay their bills. During the worst of the 2020 pandemic wave, the Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA) provided some measure of paid sick leave to workers at businesses employing fewer than 500 people, but these provisions expired at the end of the year.

The Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Fund, part of the American Rescue Plan Act, allows state, local, and tribal governments to fund paid family and medical leave for public employees. Missouri and Arkansas can and should take advantage of that fund to expand paid leave benefits to government employees, but policymakers in these states should also take the next logical step and enact a statewide paid family and medical leave law. The National Partnership for Women and Families estimates that at least 60%of working adults in Missouri and Arkansas are ineligible for unpaid leave under the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA). Further, Black and Latinx workers and women tend to be paid less, have fewer workplace protections, and are also less likely to receive paid sick leave to take care of themselves or loved ones due to occupational segregation. Paid sick leave and paid family and medical leave policies would allow workers to stay home, reducing the spread of the disease and enabling them to care for family members who may become ill. It’s the economically smart decision for Missouri and Arkansas legislators to make, and also the humane one.

Federal resources for states and local communities are available to restore critical public services, expand water, sewer, and broadband infrastructure, and provide much needed economic relief. State policymakers and local governments must use this opportunity to prioritize relief and recovery for the communities most impacted by the pandemic and advance equitable policies that strengthen public health for communities across Arkansas and Missouri for the long haul.