José Mario Antonio Milla can remember a time when he could count on the rain. In La Laguna, a hamlet of about 60 families in western Honduras, showers used to start at the end of April and continue through November, ensuring a healthy harvest of corn to feed his family. In good years, he sometimes had a small amount left over to sell. Now it’s already June, and not a drop has fallen on his 2 acres or so of land, he says. Forecasters predict a shorter rainy season this year, which has the 52-year-old farmer wondering if his six-person household will have enough to eat.

Families in La Laguna used to produce as much as 8 tons of corn a year but now have to settle for about a third of that, Milla says. “That was in the old days, 15 or 20 years ago. No one harvests those quantities anymore.” Several of his neighbors and relatives have quit trying to wring a living off the land and have moved to the cities, while others hired coyotes to smuggle them into the U.S.

Two of Milla’s sisters are living in Pennsylvania, and a brother has hopped around several states. Says Milla: “When things get bad, people leave. But the coyotes often deceive them, and then they’re right back here again.”

Working the fields outside the town of Intibucá, Honduras.

Photographer: Francesca Volpi

The so-called Northern Triangle is plagued by chronic violence, corrupt governments, and a lack of economic opportunities—factors that send a more than 300,000 thousand El Salvadorans, Guatemalans, and Hondurans fleeing their countries each year, according to estimates by academics at the University of Texas at Austin. Farmers, who in some of these nations make up as much as 30% of the population, are battling another menace: extreme weather.

Central America is among the most vulnerable regions on the planet to climate change, despite producing less than 1% of global carbon emissions, according to the World Bank. Residents of the Northern Triangle have endured five drought years over the past decade. In 2018 alone, a dry spell caused crop losses for at least 2.2 million people, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Most of them were subsistence farmers with no crop insurance who were growing corn and beans. Last year’s Hurricanes Eta and Iota destroyed homes, crops, and roads, affecting 8 million people across Central America. Additionally, infections such as leaf rust, exacerbated by climate change, are increasingly killing coffee crops, one of the region’s top exports.

“These consecutive years of extreme drought are really driving poverty and food insecurity in the region and pushing families to abandon agriculture and to migrate to survive,” says Marie-Soleil Turmel, a soil scientist with Catholic Relief Services, which works with farmers in the area. “Whole communities are being wiped out.”

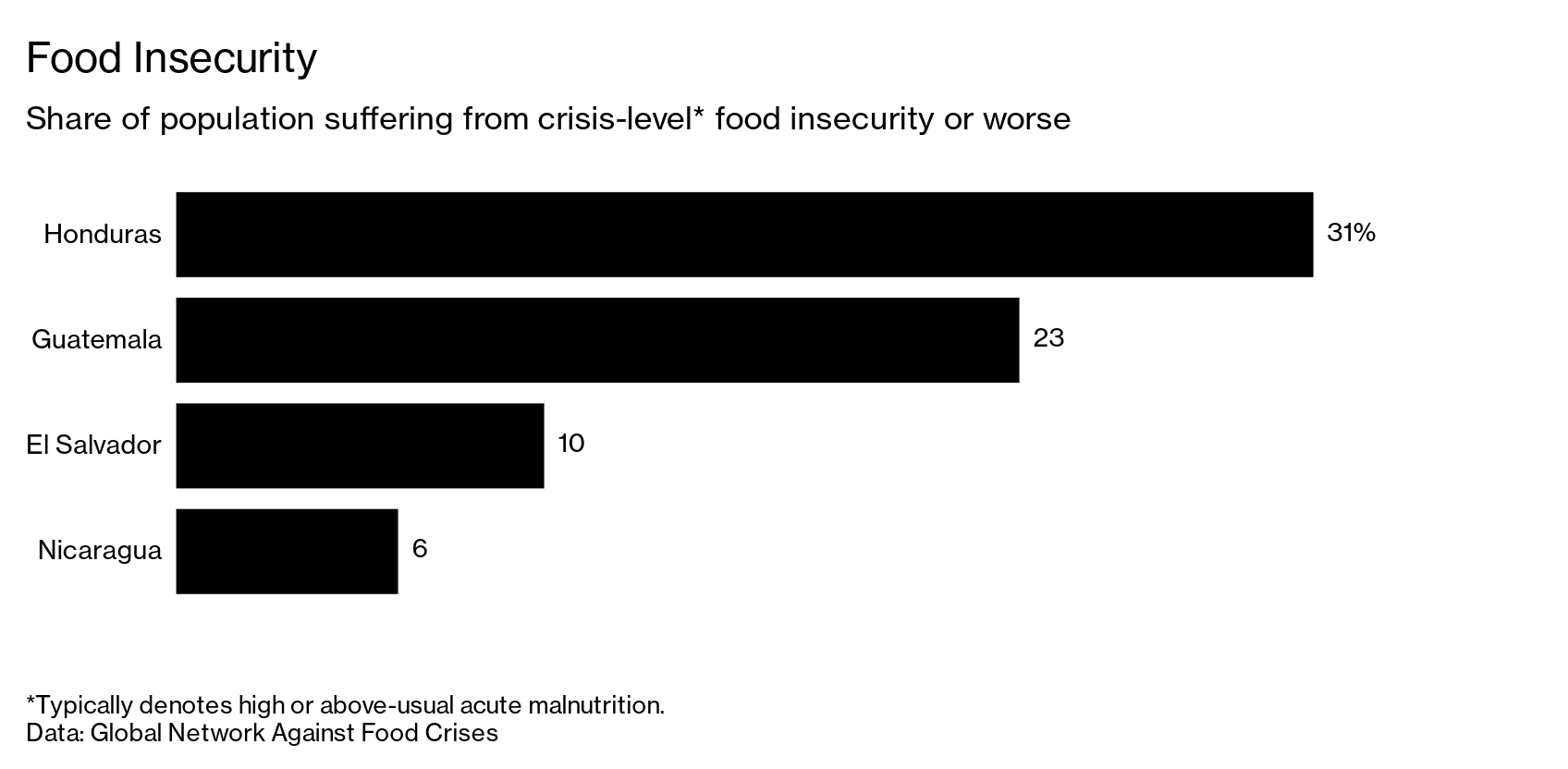

Food Insecurity

Share of population suffering from crisis-level* food insecurity or worse

*Typically denotes high or above-usual acute malnutrition.

The devastation has left millions in need of food assistance. In Honduras, 31% of the population is experiencing crisis levels of food insecurity, as is 23% in Guatemala and 10% in El Salvador, according to the UN’s global report on food crises

Flooding caused by Eta and Iota, which hit two weeks apart, destroyed Vicenta De León’s entire corn patch in Chajul, Guatemala, and killed her chickens, turkeys, pigs, and a horse. Several dozen homes were washed away in the town of 45,000 people, she says. While de León is trying to rebuild, some of her neighbors have left altogether, possibly en route to the U.S.

A farmer in Guatemala’s Baja Verapaz department. Lower harvests have forced some households to sell their livestock.

Photographer: Miguel Juarez Lugo/Zuma Press

“There is no harvest this year because we lost everything,” says the 43-year-old. De León and her husband now work odd jobs around town to support their six children but have been forced to cut back portions at meal times. “We’re doing everything we can to make money, but it’s not enough,” she says.

The Biden administration has pledged $4 billion over four years to help tackle the root causes of migration from Central America, including the climate crisis. In April, Vice President Kamala Harris also announced $310 million in humanitarian assistance for the countries in the region. “One of the areas of focus for us is the issue of hunger, hurricanes, pandemic and what these acute factors have caused in terms of the reason for the migration that we are seeing,” said Harris during a state visit to Guatemala yesterday. “They are leaving not because they want to but because they have no resources.”

In her first state visit, U.S. Vice President Kamala Harris met with Guatemalan President Alejandro Giammattei on June 7.

Photographer: Carlos Barria/Reuters

Since the start of the year, U.S. authorities have

apprehended or denied entry to more than 200,000 Central American at the southern U.S. border, expelling many of them to Mexico.

A study published in April by the Inter-American Development Bank, the Universidad de los Andes, and the University of Colorado Denver found migration from El Salvador rose after a severe drought in 2014-15, with more households reporting they had family members in the U.S. The International Organization for Migration (IOM) has also found a positive correlation between hurricanes and migration to the U.S. from the region. While some weather events are unavoidable, investing in mitigation like building stronger infrastructure, planting more resilient crops, and diversifying economies so towns are less dependent on climate-sensitive jobs could help soften the blow, according to Pablo Escribano, IOM’s regional specialist on migration, the environment, and climate change.

“Some degree of migration is going to be inevitable and some areas of Central America are going to become uninhabitable,” he says. Still, “the projections are for more intense and more frequent hurricanes, and some areas of Central America will see drought conditions increase. The situation is very challenging.”

Back in La Laguna, Milla can at least count on the $100 his sisters send him every few months, which helps buy food and household items. He says he wants to keep farming as long as he can and is experimenting with different irrigation methods and fertilizers to increase crop yields. He would consider moving to the U.S. if he’s able to secure a visa and working permits. “It’s hard to make extra money here to survive, so that’s why people leave,” he says. “Everyone here lives off their harvests and that depends on the rain.”