The Marriner S. Eccles Federal Reserve building in Washington, D.C., on April 8, 2019. Photographer: Andrew Harrer/Bloomberg

Photographer: Andrew Harrer/Bloomberg

Robots are on their way to cracking one of the world’s toughest codes: central banker speak.

In a matter of seconds, machines that mimic the human brain can read through dense and obscure policy statements and then offer a prediction. The humans who develop and use them say artificial intelligence gets it right, more often than not.

Robots that learn as they go “not only analyze communications faster than humans, but also mitigate several human shortcomings,” said Evan Schnidman, the founder of St. Louis-based Prattle Analytics LLC, which develops and sells computer-generated research on 15 central banks to hedge fund clients on Wall Street. “Human confirmation bias can lead to substantial analytical errors.”

For central bankers who have long thrived on wielding the power of words, growing use of the technology means they’ll need to pay even closer attention to their language choices, especially if computers seize on historical patterns humans tend to miss. Some central banks are already starting to vet communications through machines to gauge how they’ll be interpreted, although Prattle wouldn’t reveal which ones.

Evan Schnidman

Source: Prattle Analytics LLC

Schnidman, who did a PhD at Brown University on how central bank communications impact financial markets before starting Prattle in 2014, charges $60,000 a year for three to five users to access analysis.

It takes about 45 seconds for the neural network of Prattle’s robots to read a 500-word statement and map the words over 80 billion connections to learn how the language is interconnected. It then draws on all prior language from that central bank to determine the likely market impact. For Federal Reserve minutes, it’s even faster: clients start receiving analysis in less than a millisecond.

This speed is one of the key reasons why advances in artificial intelligence are upending an area of research that, until a few years ago, might have seemed impossible to do without human common sense.

That’s because the task requires not only swiftness, but creativity. Policy makers have historically been hard to understand, partly because of the complexity of the topic and sometimes deliberately. Former Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan said in 1987 he’d “learned to mumble with great incoherence.”

These days central bankers are, generally speaking, trying to make their communications more transparent for a broad audience; on becoming Fed Chairman, Jerome Powell said he would attempt to communicate in “plain-English’’ and doubled the number of press conferences.

Policy makers have long been aware that their words can be as powerful as their actions for influencing markets. Bank of England Governor Mervyn King illustrated this in 2005 with his “Maradona theory of interest rates.” He was inspired by Argentinian soccer player Diego Maradona, who in the 1986 World Cup dumbfounded five English players to score despite running in a straight line.

Diego Maradona, center, dribbles past three English defenders during their World Cup quarterfinal soccer match in Mexico City June 22, 1986.

Photographer: Staff/AFP via Getty Images

King’s point was that England’s defense expected Maradona to swerve, so he didn’t have to. Likewise, if investors expect the central bank to adjust policy to control inflation, markets will tighten or loosen by themselves, and the bank doesn’t have to act.

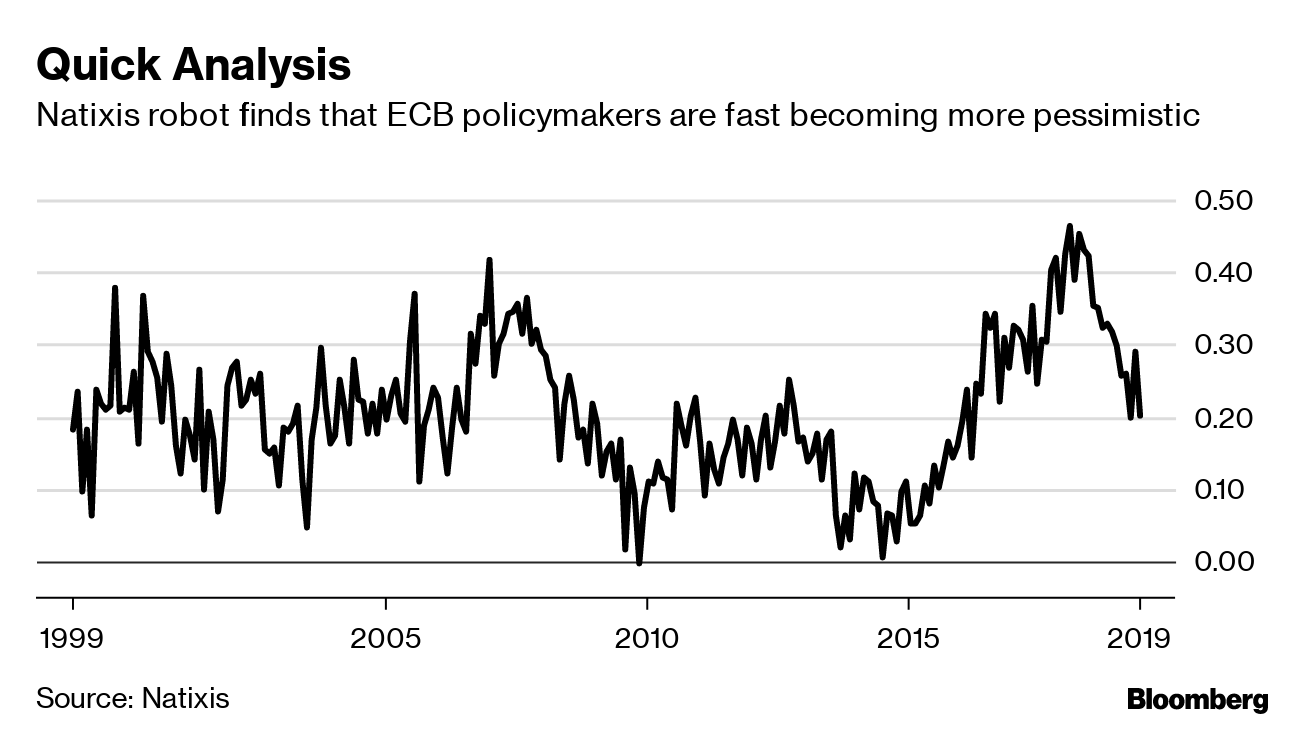

But robots aren’t that smart yet, according to Dirk Schumacher, a Frankfurt-based economist at French lender Natixis SA, which this month started publishing an automated sentiment index of European Central Bank meeting statements.

“The question is how intelligent it can become,” he said. “Maybe in a few years time we’ll have algorithms which get everything right, but at this stage I find it a nice crosscheck to verify one’s own assessments.”

Quick Analysis

Natixis robot finds that ECB policymakers are fast becoming more pessimistic

Source: Natixis

The main edge humans still have over machines is being able to read and understand ambiguity, Schumacher said. While Natixis’ system can quantify how optimistic or pessimistic ECB policy makers are looking at word choice and intensity, it can’t discern if a policy maker said something ironic — although arguably not all humans could either.

“It’s not a perfect science and it’s hard to see that humans will be replaced by these methods anytime soon,” said Elisabetta Basilico, an investment adviser who

writes about quantitative finance.

Still, the technology is developing fast and over time it could conceivably be able to grasp more nuanced communication like sarcasm, metaphor and humor.

Prattle, which was recently acquired by Liquidnet, claims its software accurately predicts G10 interest rate moves 9.7 times out of 10. The system creates a unique lexicon for each central bank board member and analyzes language patterns over time, according to Schnidman. He said it’s able to control for Chicago Fed President Charles Evans’ frequent use of so-called straw-man arguments, a rhetorical device that deliberately exaggerates an opponent’s position to undermine it. A Chicago Fed spokeswoman declined to comment.

The algorithm used by Nordea Bank Abp, the largest lender in the Nordic region, is sharp enough to notice if a sentence sticks out from the rest of the text, according to Kristin Magnusson Bernard, Nordea’s global head of macro research. Backtesting shows it would have picked up on the importance of the famous three words, “whatever it takes,” ECB President Mario Draghi uttered in July 2012 that ultimately saved the euro from collapse.

“The question is what would happen if a central bank would completely rework its communication approach,” she said. “Then it would be interesting if a human or an algorithm would be faster at finding the core meaning of it.”

Sofia Frojd works on the trading floor at Nordea Bank Abp in Stockholm.

Photographer: Mikael Sjoberg/Bloomberg

For now, human analysts are keeping their jobs — but admit to paying more attention to their biases: whether they are just seeking to confirm previously held beliefs or following gut feelings that aren’t backed by facts.

And banks are hiring programmers to develop software in-house, people like 26-year-old Master’s graduate Sofia Frojd, the brains behind Nordea’s self-learning algorithm, which offers analysis on the Bank of England, the ECB and the local Riksbank, among others. The system churns out charts almost instantly, including a “hawk-o-meter” measuring whether central bankers favor higher interest rates to contain inflation or lower rates to spur the economy.

The Riksbank’s next move will be a rate rise, but not for a very long time, according to both the robot, whose electronic brain was uploaded with communications go back to the 1990s, and Nordea’s main Riksbank analyst Torbjorn Isaksson.

“I hardly have the time to open the PDF file from the Riksbank before Sofia says ‘it’s ready’,” Isaksson said. “It will continue to develop over time, which is a bit scary for a Riksbank analyst.”

— With assistance by Paul Gordon, and Matthew Boesler