A strong dollar is hurting American workers and main street manufacturers, as I explained last week in the New York Times. I discussed what can be done about it, which builds on a crucial plank of Elizabeth Warren’s American Jobs plan.

In order to rebalance U.S. trade, the dollar needs to fall 25–30 percent, especially against the currencies of countries with large, persistent trade surpluses such as China, Japan, and the European Union. This would help to address the trade deficits that have eliminated nearly 5 million good-paying American manufacturing jobs over the past two decades and some 90,000 factories. In fact, trade with low-wage countries has pulled down the incomes of 100 million non-college educated workers by roughly $2,000 per year.

This week, Ruchir Sharma of Morgan Stanley trotted out a bunch of very shaggy dogs in defense of a strong currency. But he never mentioned the real reason Wall Street loves a strong dollar. An overvalued greenback has enabled the cheap imports that fuel the massive profits of American giants ranging from Apple and Amazon to Costco and Walmart. And multinational corporations have used offshoring, and the threat of moving more plants abroad, to drive down U.S. wages and benefits, and to weaken domestic labor unions.

Sharma claims growing trade deficits bring great benefits to the United States. And he praises the financing of our budget deficits through the sale of Treasury securities to foolish foreigners who are willing to hold them—with Wall Street bond traders brokering all of those sales for hefty fees. However, there are vast amounts of excess savings available in the United States and around the world, and there are no signs of a capital shortage, as evidenced by short- and long-term interest rates that are at historic lows across developed countries. The real issue, therefore, isn’t attracting capital, but rather the loss of American jobs and productive capacity that comes from growing trade deficits.

Sharma also claims that America’s ability to sell Treasury bills abroad depends, in part, on the dollar’s status as a “reserve currency …a perk of imperial might,” as though America were some powerful kingdom, with a throne in New York. In fact, as Dean Baker points out, the “dollar is not ‘the’ reserve currency,” it is simply one among many. Baker notes that central banks also hold euros, yen, British pounds, and Swiss francs, and can easily switch from one to another. And in today’s modern global economy, there is very little need to hold costly currency reserves. For example, in January 2019, the United States held only $115 billion in total foreign exchange reserves, which was equal to less than two weeks worth of total goods and services imports.

Sharma admits that dollar realignment would boost exports and jobs, but claims that it would provide only a temporary benefit for “fading manufacturing industries.” This is a particularly troubling argument. First, as noted above manufacturing jobs (along with construction) provide excellent wages and benefits, especially for U.S. workers without a bachelor’s degree (as demonstrated in the chart below). Unfortunately, there are still 900,000 fewer jobs in these sectors than at the start of the Great Recession.

“Growing industries” such as hospitality, health care, and temporary help services—which have gained jobs since the beginning of the recession—pay substantially less than construction and manufacturing industries. Hourly pay in these job-gaining industries was $26.19 on average, versus $28.88 in in manufacturing and $31.29 construction, as shown in the figure below. Total compensation (which includes both wages and benefits) in job-gaining industries is 33.39, while compensation in manufacturing and construction is $39.53 and 39.55 respectively, 18.4 percent more than in job-gaining industries.

Lagging recovery of construction and manufacturing sectors is one more reason wage growth is suffering for most workers: Average hourly compensation in construction and manufacturing compared with industries that have gained jobs since the Great Recession

| Sector | Wages | Benefits |

|---|---|---|

| Construction | $31.29 | $8.26 |

| Manufacturing | $28.88 | $10.65 |

| All industries that have gained jobs | $26.19 | $7.20 |

Source: EPI analysis of BLS Current Employment Statistics and Employment Cost Trends public data series.

Prolonged stagnation in manufacturing and construction employment have contributed to the slow growth of wages for non-college educated workers over the past decade. Rebalancing the dollar could lead to strong growth in these sectors. And that would provide a much-needed boost to wages for working Americans.

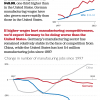

The second flaw in Sharma’s “fading” manufacturing industries is that this is not an inevitable—or desirable—trend. The steady loss of U.S. manufacturing jobs is the result of a policy choice. Germany, for example has held onto manufacturing jobs over the past 20 years, despite having higher wages for comparable workers than in the United States, as shown in the chart below. Manufacturing’s share of total employment has been stable in Germany, at about 17 percent of total employment (versus less than 10 percent in the United States), as shown in the second figure below.

China, which has been running massive trade surpluses for two decades has seen its manufacturing employment share rise. Germany held onto manufacturing jobs, in part by devaluing the euro and the EU, via the Hartz reforms, which lowered wages relative to the rest of the EU. China manipulated its currency for more than a decade, and continues to maintain an undervalued yuan by carefully managing private capital outflows. Maintaining a strong manufacturing sector and stable manufacturing employment are policy choices. And contrary to Sharma’s dismissal, it is a key driver for income generation in advanced economies.

China, which has been running massive trade surpluses for two decades has seen its manufacturing employment share rise. Germany held onto manufacturing jobs, in part by devaluing the euro and the EU, via the Hartz reforms, which lowered wages relative to the rest of the EU. China manipulated its currency for more than a decade, and continues to maintain an undervalued yuan by carefully managing private capital outflows. Maintaining a strong manufacturing sector and stable manufacturing employment are policy choices. And contrary to Sharma’s dismissal, it is a key driver for income generation in advanced economies.

While Germany and China have managed their economies to maintain and expand manufacturing employment, the United States has favored a strong dollar policy that has decimated U.S. manufacturing. But that path has also generated massive profits for Wall Street, along with rising incomes only for those at the top, including finance executives. Germany and China have invested in building up strong manufacturing sectors. In contrast, the U.S. poured massive subsidies into Wall Street (with nearly a decade of unlimited access to discount-window borrowing from the Federal Reserve at near-zero percent interest rates), with no payback or quid pro quo. Meanwhile, not a single banker went to jail in the wake of a financial crisis that rocked the global economy.

Sharma has the temerity to conclude that dollar realignment will “damage the economy.” But who benefits from this type of economy?

He has it exactly backwards. A lower dollar stimulates exports, job creation, and the growth of a strong economy with high and rising wages. The dollar was realigned by President Nixon in December 1971, and again in 1985, during the Reagan administration, following the Plaza Accord. There is no evidence that the economy slowed after either one of those events, as shown in the chart below, which tracks U.S. quarterly GDP growth since 1969 (each currency realignment is marked with dotted lines).

The time has come for a serious discussion of permanent currency realignment to rebalance global trade and capital flows. And it is time to put an end to sacrificing the national interest simply for the narrow benefit of Wall Street.

No evidence that currency realignment slowed growth : Real GDP growth, 1969 –1989

| A191RL1Q225SBEA | |

|---|---|

| 1968-Q2 | 6.9 |

| 1968-Q3 | 3.1 |

| 1968-Q4 | 1.6 |

| 1969-Q1 | 6.4 |

| 1969-Q2 | 1.2 |

| 1969-Q3 | 2.7 |

| 1969-Q4 | -1.9 |

| 1970-Q1 | -0.6 |

| 1970-Q2 | 0.6 |

| 1970-Q3 | 3.7 |

| 1970-Q4 | -4.2 |

| 1971-Q1 | 11.3 |

| 1971-Q2 | 2.2 |

| 1971-Q3 | 3.3 |

| 1971-Q4 | 0.9 |

| 1972-Q1 | 7.6 |

| 1972-Q2 | 9.4 |

| 1972-Q3 | 3.8 |

| 1972-Q4 | 6.9 |

| 1973-Q1 | 10.3 |

| 1973-Q2 | 4.4 |

| 1973-Q3 | -2.1 |

| 1973-Q4 | 3.8 |

| 1974-Q1 | -3.4 |

| 1974-Q2 | 1 |

| 1974-Q3 | -3.7 |

| 1974-Q4 | -1.5 |

| 1975-Q1 | -4.8 |

| 1975-Q2 | 2.9 |

| 1975-Q3 | 7 |

| 1975-Q4 | 5.5 |

| 1976-Q1 | 9.3 |

| 1976-Q2 | 3 |

| 1976-Q3 | 2.2 |

| 1976-Q4 | 2.9 |

| 1977-Q1 | 4.8 |

| 1977-Q2 | 8 |

| 1977-Q3 | 7.4 |

| 1977-Q4 | 0 |

| 1978-Q1 | 1.3 |

| 1978-Q2 | 16.4 |

| 1978-Q3 | 4.1 |

| 1978-Q4 | 5.5 |

| 1979-Q1 | 0.7 |

| 1979-Q2 | 0.4 |

| 1979-Q3 | 3 |

| 1979-Q4 | 1 |

| 1980-Q1 | 1.3 |

| 1980-Q2 | -8 |

| 1980-Q3 | -0.5 |

| 1980-Q4 | 7.7 |

| 1981-Q1 | 8.1 |

| 1981-Q2 | -2.9 |

| 1981-Q3 | 4.9 |

| 1981-Q4 | -4.3 |

| 1982-Q1 | -6.1 |

| 1982-Q2 | 1.8 |

| 1982-Q3 | -1.5 |

| 1982-Q4 | 0.2 |

| 1983-Q1 | 5.4 |

| 1983-Q2 | 9.4 |

| 1983-Q3 | 8.2 |

| 1983-Q4 | 8.6 |

| 1984-Q1 | 8.1 |

| 1984-Q2 | 7.1 |

| 1984-Q3 | 3.9 |

| 1984-Q4 | 3.3 |

| 1985-Q1 | 3.9 |

| 1985-Q2 | 3.6 |

| 1985-Q3 | 6.2 |

| 1985-Q4 | 3 |

| 1986-Q1 | 3.8 |

| 1986-Q2 | 1.8 |

| 1986-Q3 | 3.9 |

| 1986-Q4 | 2.2 |

| 1987-Q1 | 3 |

| 1987-Q2 | 4.4 |

| 1987-Q3 | 3.5 |

| 1987-Q4 | 7 |

| 1988-Q1 | 2.1 |

| 1988-Q2 | 5.4 |

| 1988-Q3 | 2.4 |

| 1988-Q4 | 5.4 |

| 1989-Q1 | 4.1 |

| 1989-Q2 | 3.1 |

Source: Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED) from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, accessed June 2019